11 January 2019

roadmap

austria

A glimpse into the future...

Connectivity, algorithms, artificial intelligence… more and more digitalisation becomes part of our daily lives. What does this mean from a legal perspective - blessing or curse? Data protection expert Günther Leissler asks Univ Prof Dr. Nikolaus Forgó, Head of the Department of Innovation and Digitalisation in Law, University of Vienna, for his skilled view on the subject.

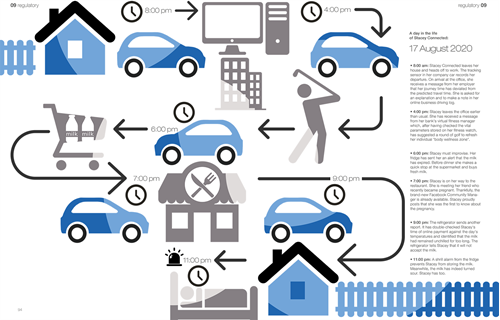

• 8:00 am: Stacey Connected leaves her house and heads off to work. The tracking sensor in her company car records her departure. On arrival at the office, she receives a message from her employer that her journey time has deviated from the predicted travel time. She is asked for an explanation and to make a note in her online business driving log.

• 4:00 pm: Stacey leaves the office earlier than usual. She has received a message from her bank's virtual fitness manager which, after having checked the vital parameters stored on her fitness watch, has suggested a round of golf to refresh her individual "body wellness zone".

• 6:00 pm: Stacey must improvise. Her fridge has sent her an alert that the milk has expired. Before dinner she makes a quick stop at the supermarket and buys fresh milk.

• 7:00 pm: Stacey is on her way to the restaurant. She is meeting her friend who recently became pregnant. Thankfully, the brand-new Facebook Community Manager is already available. Stacey proudly posts that she was the first to know about the pregnancy.

• 9:00 pm: The refrigerator sends another report. It has double-checked Stacey's time of online payment against the day's temperatures and identified that the milk had remained unchilled for too long. The refrigerator tells Stacey that it will not accept the milk.

• 11:00 pm: A shrill alarm from the fridge prevents Stacey from storing the milk. Meanwhile, the milk has indeed turned sour. Stacey has too.

Interview with Univ. Prof. Dr. Nikolaus Forgó, Head of the Department of Innovation and Digitalisation in Law, University of Vienna

Q: There is a tracking sensor in Stacey Connected's car. With this sensor, her employer records Stacey as soon as she leaves the house. The example shows: Digitalisation might increasingly lead to employers intruding in their employees' privacy. Do you think such an increase is realistic and do you see a need to make labour law "digitalisation-proof"?

A: I don't think labour law deserves particular attention here. Digitalisation creates plenty of new challenges in other areas of law too, such as consumer protection, intellectual property or data protection. Already today, the example of the tracking sensor would only be permitted under current data protection law if Stacey has provided her individual, informed consent.

Many companies are offering more and more services in addition to their core business. Stacey's bank provides a Wellness Manager, which means the bank receives health data of its customers. Do you consider such connectivity legitimate?

Such connectivity is widespread in many areas even today. We have surprisingly quickly become accustomed to business models based on "data in exchange for (seemingly) free services". These models are often based on consent. The GDPR has now established more rigid requirements – at least on paper – by stipulating in Art. 7 para 4 that consent is not to be regarded as voluntarily given if it is given for data processing not required for the contractual service. The meaning and scope of this prohibition to couple consent (Koppelungsverbot) is controversial; recently the Austrian Supreme Court expressed a very rigid view. But I predict that business models such as Stacey's "Wellness Manager" will remain legitimate. Nevertheless, an important legal and economic problem arises from the fact that such tools require enormous data resources, which often are not in the hands of European companies and this might prevent them from market entries. It may be necessary to respond with competition and antitrust laws.

Stacey's refrigerator guides her through her day, forming part of the Internet of Things (IoT) chain. Do you think such scenarios can be expected soon? If so, where do you see the main legal challenges?

Algorithms that take decisions out of our hands or at least influence them are already part of our lives. From Google Maps to shopping recommendations by Amazon, we have become accustomed to our decisions being automatically prepared and simplified. It's only a small step until automatic decisions will be made completely autonomously. This will lead to interesting legal questions, like who will have to take responsibility for damages caused by such systems. This can be the manufacturer (e.g. by amending the product liability law), the user, the owner, the injured party, or even the public. On the other hand, we must consider how much autonomy we want to grant such systems. It must be made clear, for example, whether and under what conditions a person can (and must) overrule machine-made decisions.

Stacey posts about her friend's pregnancy without her friend's knowledge. Is this a violation of privacy and of data protection laws?

Yes, of course. The posting means the publishing of Stacey's friend's sensitive personal data. We have known for 20 years that data protection law makes this generally inadmissible, also thanks to one of the first decisions of the European Court of Justice on data protection law (C-101/01, Lindqvist). At that time, it was about a broken leg, not a pregnancy, but the ECJ's considerations are equally if not even more applicable to Stacey's posting.

Stacey's refrigerator does not accept the milk she bought. How do you think it should be handled if intelligent devices do not cooperate but block each other?

This will probably have to be decided on a case-by-case basis, primarily against the background of (pre)contractual duties of care. However, I do not expect fundamental problems here, as such questions can be compared with already existing situations of conflicting general terms and conditions – and the legal solutions in place for such conflicts.

Stacey's refrigerator detects that she has not properly handled her milk while she was on the move. From the supermarket's perspective, such a piece of information potentially helps in rejecting warranty claims. Although this example refers to an everyday purchase only, it underlines the value that IoT data could have in the future. Do you think future legal disputes will revolve around the disclosure of data?

The economic importance of data, including raw data, is certainly increasing – so you are right when generally referring to "information". However, in light of the increasing economic value of such information, one should not mistakenly conclude that new legal concepts have to be created, such as data property rights, or even ask for the ABGB to be amended. Questions like who will enjoy legal protection – and why and to what extent – require complex considerations to ensure overall fair use of information. You shouldn't try to solve them hastily. Not least since much of what we are now discussing can be solved with already existing legal instruments.

At the end of the day, despite all the technology that supposedly makes her life easier, Stacey gets annoyed. In your opinion, is digitalisation a blessing or a curse?

Without doubt, a blessing! We have been given useful tools to increase our efficiency, our ability to communicate, and our autonomy. What remains is to use them in a thoughtful manner. History has proven that despite all distortions, technology and its developments have always been to humanity's advantage. Why should it be different this time?

Thank you for the interview.

-----

This article was up to date as at the date of going to publishing on 10 December 2018.

Günther

Leissler

Partner

austria vienna