Artificial intelligence (AI) is shaping our world, and the European Union (EU) aims to become a world-class hub for AI and to ensure that AI is human-centric and trustworthy.

The EU is further trying to foster a European economy that is well-positioned to benefit from the potential of AI, not only as a user, but also as a creator and producer of this technology. It encourages research centres and innovative start-ups to take a world-leading position in AI and competitive manufacturing and services sectors, from automotive to healthcare, energy, financial services and agriculture.

AI is not only a great opportunity but also a huge challenge for businesses, from facing the need to transform to contending with new risks, liabilities and regulations. AI will also affect almost every industry.

Due to complex, multidisciplinary legal issues, new and innovative approaches must be taken.

our services

With our AI Task Force, we have specialised experts in navigating the complexities of AI and the evolving regulatory landscape. Here's how we can help:

- Privacy and security: We will conduct privacy assessments and set up data governance programmes, protecting your AI projects within the limits of data protection laws.

- Intellectual property: Protect and license your AI-related IP, including IP generated by AI technology, with our comprehensive services.

- Contract support: We will draft, negotiate and defend your AI contracts, and assist with AI start-up agreements and governance.

- Business model legal analysis: Our team will analyse your AI-enabled business model, ensuring compliance with civil, consumer protection and e-commerce laws.

- Regulatory representation: We will represent you before European and local authorities and courts, addressing data protection inquiries or AI-specific regulations.

- M&A due diligence: We will conduct thorough due diligence on AI-related companies in the context of mergers or acquisitions.

- Future-proof legal solutions: Stay ahead of the curve with our forward-looking solutions for emerging legal challenges in the AI landscape.

- Consumer law implications: We will help you navigate the consumer law implications for your digital business, ensuring transparency and compliance.

- EU AI Act compliance: We will guide you through the upcoming EU AI Act, ensuring your business meets its requirements and mitigates risks in a timely manner.

- Customised AI support: Whether it is AI software for recruitment or data rights from autonomous vehicles, we will provide tailored legal advice.

Our multidisciplinary approach, combining legal and IT expertise, provides comprehensive advice on your AI initiatives, ensuring that you are prepared for tomorrow's legal challenges.

For a comprehensive overview of artificial intelligence, please see below.

What does AI mean?

The details about AI

In the last decade, AI has increasingly gained awareness on the consumer end. promising stories in the news media to the ubiquitous use of large search engines, AI has not only become part of our everyday lives but seems to be all encompassing. From cars to toasters, everything these days is "powered by AI" (or at least claims to be so). And everyone seems to be talking and thinking about the problems and opportunities associated with AI, no matter the field. Once relegated to niche scientists and science fiction aficionados, AI has now gone fully mainstream.

This has not gone unnoticed by eager regulators (and us, of course):

The EU Commission has drafted a tightly knit regulation on AI. But other jurisdictions are also seeing the need for specific rules. In the US, 2022 saw the emergence of an initial approach to regulate AI, focused on specific AI use cases. But more general AI regulatory initiatives may arrive in 2023, including the state data privacy law, FTC (Federal Trade Commission) rulemaking, and new NIST (National Institute for Standards and Technology) AI standards. In June 2022, the Canadian government introduced Bill C-27, the Digital Charter Implementation Act, 2022. Bill C-27 proposes, among other things, to enact the Artificial Intelligence and Data Act (AIDA). Although there have been previous efforts to regulate automated decision-making as part of federal privacy reform efforts, AIDA is Canada's first effort to regulate AI systems outside of privacy legislation. In October 2022, the Israeli Ministry of Innovation Science and Technology released its "Principles of Policy, Regulation and Ethics in AI" white paper for public consultation, which sets forth policy, ethics and regulatory policy recommendations.

AI from a scientific perspective

AI as a field of scientific research has existed for quite some time. Still, no definition of AI has emerged that even computer scientists can agree on. In their textbook Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach, Russell and Norvig offer four rough groups of definitions:

- Programs that think like humans.

- Programs that behave like humans

- Programs that behave rationally

- Programs that think rationally.

In the end, Russell and Norvig settled on AI thinking rationally being the most helpful group of definitions in the light of the modern-day approach to the term. This definition demands of a program to react in a rational way to input it has never seen before by giving the output with the highest probability of success. As such an input-output relationship would usually not be hard coded, programs fulfilling this definition would usually have to learn and extrapolate based on previous input.

However, there are still a wide range of algorithms that check this box. Even linear regressions could therefore lead to an AI (e.g. a program that extrapolates an estimated house price based on house size via linear regression based on historic – known – price-size value pairs in the same region).

The modern-day discussion has, however, been triggered by one particular class of algorithms: neural networks.

in application in the last 10-20 years. Originating from the idea of algorithmically implementing a simplified model of how human brain cells work, it has meanwhile been proven that a sufficiently advanced neural network may implement any mathematical function to an arbitrary degree of precision. In other words, given enough calculating power and time, almost any real-world problem can be solved by a neural network.

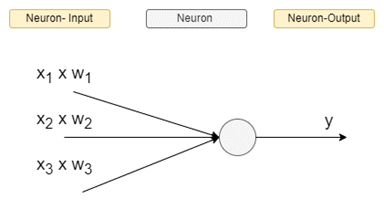

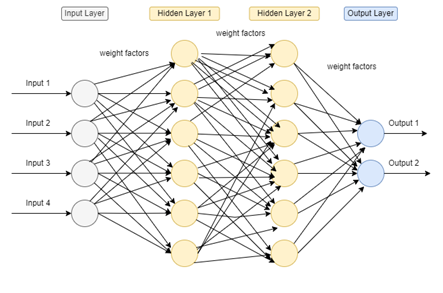

As originally indicated, a simple neural network consists of multiple "neurons" mapping multiple inputs (x) to a single output (usually between 0 and 1). This is achieved by applying a certain weight factor (w) to every input (w*x), the sum of which together with a constant ("b" – called the bias) is then fed into the neuron (z = Σ wi x xi + b).

The neuron's job is then to apply a certain fixed function (the activation function) to the weighted sum of all inputs (z) producing an output (y) between 0 and 1.

This simple algorithm could run in parallel, forming a layer, and multiple such layers could be chained so that the inputs x would be the original outputs from other neurons and output y would further be one of the inputs of multiple neurons of the next layer until the final layer (the "output layer is reached"). Layers in between the first layer (the "input layer") and the output layer are called hidden layers, since their behaviour is usually not visible to the informed user or any program utilising the neural network.

While the topology of the number of layers and the number of neurons per layer are determined by a skilled developer, the biases and weights applied to each neuron's output are to be trained by a program implementing a machine learning algorithm.

As already alluded to with regards to neural networks, the heavy lifting in the last decades of the AI revolution was enabled not by neural networks themselves but by means of their efficient training. This is the field of machine learning.

Machine learning is a crucial component of AI that focuses on the automated examination finding of patterns in seemingly arbitrary data sets. Therefore, it enables any AI trained by a machine learning program to implement the logic (or more specifically, the mathematical function) inherent in any data set to be analysed, without any detailed human instruction.

Therefore, the field of machine learning enables computers to comprehend data and their relationships, thereby empowering them to execute specific tasks. By analysing multiple data points to recognise patterns over time, machine learning provides the foundation for technology to eventually make decisions or offer suggestions. Unlike traditional computers that necessitated explicit directions for every aspect of a task, AI-powered machines can now learn on their own, eliminating the need to be instructed for every task. This represents a significant departure from the previous model, where machines were required to be taught every aspect of a task.

Example:

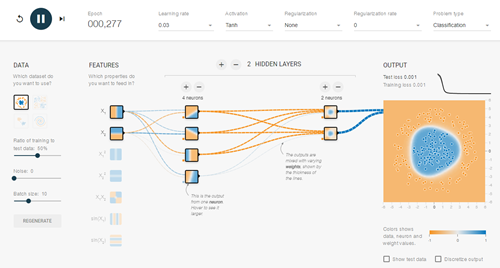

Source: TensorFlow

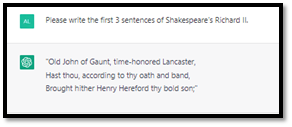

ChatGPT is a large language model developed by OpenAI. It utilises machine learning to answer text-based questions and perform tasks relevant to human language. ChatGPT is capable of understanding a wide range of topics and responding to them, including history, technology, science, art and more. It can also engage in conversations and generate text on request.

Natural language processing (NLP) focuses on the ability of computers to understand and process human language. It allows computers to extract and analyse language data, making it easier for users to search for information using natural language phrases and sentences, rather than specific keywords. NLP can improve search results by providing a more intuitive and human-like search experience, and by incorporating machine learning algorithms that can understand the context of the user's query and return results that are more relevant to their needs.

ChatGPT and search engines are both AI-powered systems, but they serve different purposes and work in different ways.

ChatGPT is a language model that is trained to generate text based on the input it receives. It uses a neural network architecture called a transformer, which allows it to understand the context and generate a response that is relevant to the input. ChatGPT has been trained on a large corpus of text data, which enables it to generate responses to a wide range of questions and topics.

On the other hand, a search engine is a tool that helps users find information on the internet. When a user enters a query into a search engine, it uses a complex algorithm to search through billions of webpages and return the most relevant results. The algorithm takes into account various factors, such as the relevance of the page content, the authority of the website, and the user's location and search history. The search engine then ranks the results based on their relevance and displays them to the user.

In summary, ChatGPT is a language model that generates text, while a search engine is a tool that helps users find information on the web.

Data mining is the process of discovering patterns, correlations and insights in large data sets by analysing and modelling the data. Technology systems scour data and recognise anomalies within the data at a scale that would be impossible for humans. It helps organisations make more informed decisions by uncovering patterns and insights that may not be immediately apparent. The benefits of data mining can be seen in areas such as online recommendations, document review, healthcare and finance.

AI from a tech lawyer's perspective

On the one hand, lawyers analyse the legal issues that arise with the use of AI. They deal with the direct AI regulation and with the indirect AI regulation through liability. For example, the risk classification of the AI software used or the contractual relationship between the user and the AI manufacturer.

On the other hand, lawyers are always looking to improve their own services and are trying to do so by using AI solutions. Thus, the number of legal tech AI applications is steadily on the rise. For example, lawyers are using machine learning software for document analysis. This helps them to analyse contracts and other legal documents efficiently and quickly. AI is also being used to automate and standardise contract drafting.

AI from a regulatory perspective: the EU AI Act

For regulators, AI refers to the use of advanced computer algorithms and machine learning techniques to simulate human intelligence and automate decision-making processes. Regulators are concerned with ensuring the safety, fairness and ethical use of AI in various industries, such as finance, healthcare and transportation. This may involve setting standards and guidelines for the development and deployment of AI systems, monitoring their performance, and taking action to address any negative impacts they may have on society.

Overall, the goal of regulators is to ensure that AI is developed and deployed in a responsible and ethical manner that promotes innovation while also protecting public interests.

AI is seen as a potentially transformative technology that can bring both benefits and risks. Regulators are tasked with balancing the promotion of innovation and the protection of public interests. In order to do so, they often focus on the following areas related to AI:

- Data privacy and security: Ensuring that personal and sensitive information is collected, stored and processed in a secure and ethical manner.

- Bias and fairness: Addressing the potential for AI systems to reinforce existing biases or discriminate against certain groups.

- Transparency and accountability: Requiring AI systems to be transparent and explainable, and holding their creators accountable for any negative outcomes.

- Testing and certification: Developing and enforcing standards for testing and certifying the safety, performance and ethical use of AI systems.

- Consumer protection: Protecting consumers from any potential harm that may result from the use of AI, such as financial loss or physical harm.

Overall, the goal of regulators is to ensure that AI is developed and deployed in a responsible and ethical manner that promotes innovation while also protecting public interests.

The AI Act has the potential to become a global standard, shaping the impact of AI on individuals across the world, similarly to how the EU's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) did in 2018. The EU's regulation of AI is already having a significant impact internationally, with Brazil recently passing a bill that establishes a legal framework for AI use. AI has a major impact on people's lives by affecting the information they see online through personalisation algorithms, analysing faces for law enforcement purposes, and aiding in the diagnosis and treatment of illnesses such as cancer.

The Act takes a "horizontal" approach and sets out harmonised rules for developing, placing on the market and using AI in the EU. The Act draws heavily on the model of "safe" product certification used for many non-AI products in the new regulatory framework. It is part of a series of draft EU proposals to regulate AI, including the Machinery Regulation and product liability reforms. The law needs to be read in the context of other major packages announced by the EU, such as the Digital Services Act, the Digital Markets Act and the Data Governance Act. The first two are primarily concerned with the regulation of very large commercial online platforms. The AI Act does not replace the protections offered by the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), but will overlap with them, although the scope of the former is broader and is not limited to personal data. The AI Act also draws on the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive for parts relating to manipulation and deception. Existing consumer protection law and national laws, such as tort law, are also relevant.

In a nutshell, the AI Act aims to govern the development and utilisation of AI systems deemed as "high risk" by setting standards and responsibilities for AI technology providers, developers and professional users. Certain harmful AI systems are also prohibited under the Act. The Act encompasses a broad definition of AI and distinguishes it from traditional IT. There is ongoing debate in the EU Parliament on the need for a definition for General Purpose AI. The Act is designed to be technologically neutral and future-proof, potentially affecting providers as greatly as the GDPR did. Non-compliance with the Act could result in penalties of up to EUR 30m or 6 % of the provider's or user's worldwide revenue for violations of prohibited practices.

Businesses need to determine if their AI systems fall within the scope of the legislation and conduct risk assessments of their AI systems. If they are using high-risk AI systems, they must establish a regulatory framework, including regular risk assessments, data processing impact assessments and detailed record-keeping.

The AI systems must also be designed for transparency and explainability. The terms of use for these systems are deemed crucial for regulating high-risk AI systems, requiring a review of contracts, user manuals, end-user licence agreements and master service agreements in light of the new legislation.

The AI Act outlines key terms and definitions related to AI systems and their usage. Below you will find a detailed explanation of the most material terms:

- Artificial Intelligence System (AI system) – This term refers to software that is created using one or more techniques mentioned in Annex I of the AI Act. AI systems generate outputs such as content, predictions, recommendations or decisions that influence their surroundings and the environments they interact with. Annex I of the AI Act provides a comprehensive list of software that is considered AI systems, such as machine learning, statistical approaches, logic and knowledge-based approaches.

- Provider – A provider is defined as a natural or legal person, public authority, agency or other body that creates or commissions the creation of an AI system for commercialisation or deployment. This includes those who sell or deploy the AI system under their name or trademark, whether for money or for free.

- Importer – An importer refers to any natural or legal person based in the EU who sells or uses an AI system bearing the name or trademark of a person based outside the EU.

- User – A user refers to any natural or legal person, public authority, agency or other body that uses an AI system under their control, except in cases of personal, non-professional activity.

- Authorised Representative – This term refers to a natural or legal person established in the EU who has been granted written permission by the creator of an AI system to carry out their duties and processes specified by the Regulation.

- Law Enforcement – This refers to actions taken by law enforcement officials to prevent, investigate, uncover or bring criminal charges or carry out criminal sentences, as well as to defend against and prevent threats to public safety.

- National Supervisory Authority – This term refers to the body designated by a Member State to enforce and carry out the Regulation, coordinate assigned tasks, serve as the Commission's sole point of contact and speak on behalf of the Member State at the European Artificial Intelligence Board.

It is crucial to understand these definitions in order to fully comprehend the AI Act and its implications for AI systems and their usage.

The Regulatory Framework defines four levels of risk in AI:

Many countries are currently working on regulatory frameworks for AI, including the USA, Canada, Israel and the European Union. The latter has published (and amended) its draft AI Act. The AI Act splits AI into four different bands of risk based on the intended use of a system. Of these four categories, the AI Act is most concerned with "high-risk AI", but it also contains a number of "red lines". These are AIs that should be banned because they pose an unacceptable risk.

Prohibited AI applications are considered unacceptable as being in conflict with the values of the Union, for example due to the violation of fundamental rights. These include AI that uses subliminal techniques to significantly distort a person's behaviour in a way that causes or is likely to cause physical or psychological harm. AI that enables manipulation, social scoring and "real-time" remote biometric identification systems in "public spaces" used by law enforcement is also prohibited.

The Act follows a risk-based approach and implements a modern enforcement mechanism, where stricter rules are imposed as the risk level increases. The AI Act establishes a comprehensive "product safety framework" based on four levels of risk. It requires the certification and market entry of high-risk AI systems through a mandatory CE-marking process and extends to machine learning training, testing and validation datasets. For certain systems, an external notified body may participate in the conformity assessment evaluation. Simply put, high-risk AI systems must go through an approved conformity assessment and comply with the AI requirements outlined in the AI Act throughout their lifespan.

What are examples of high-risk AI?

Examples of high-risk AI systems that will be subject to close examination before being put on the market and throughout their lifespan include:

- critical infrastructures such as transportation that could endanger the lives and health of citizens;

- education and vocational training that could influence someone's access to education and career path;

- safety components of products, such as AI in robot-assisted surgery;

- employment management and access to self-employment, such as CV sorting software in recruitment;

- essential public and private services, such as credit scoring that could impact citizens' ability to obtain loans;

- law enforcement that could infringe upon people's basic rights, such as evaluating the reliability of evidence;

- migration and border control management, such as verifying the authenticity of travel documents;

- administration of justice and democratic processes, such as applying the law to specific facts;

- surveillance systems, such as biometric monitoring and facial recognition systems used by law enforcement.

The AI Act outlines a four-step process for the market entry of high-risk AI systems and their components. Those steps are:

- development of the high-risk AI system, ideally through internal AI impact assessments and codes of conduct, overseen by inclusive and multidisciplinary teams;

- approved conformity assessment and ongoing compliance with the requirements of the AI Act throughout the system's lifecycle; external notified bodies may be involved in certain cases;

- registration of the high-risk AI system in a dedicated EU database;

- signing of a declaration of conformity and carrying the CE marking, allowing the system to be sold in the European market.

But that's not all…

After the high-risk AI system has received market approval, ongoing monitoring is still necessary. Authorities at both the EU and Member State levels will be responsible for market surveillance, while end-users will ensure monitoring and human oversight, and providers will have a post-market monitoring system in place. Any serious incidents or malfunctions must be reported. This means ongoing upstream and downstream monitoring is required.

The AI Act also imposes transparency obligations on both users and providers of AI systems, including bot disclosure and specific obligations for automated emotion recognition systems, biometric categorisation and deepfake/synthetic disclosure. Only minimal risk AI systems are exempt from these transparency obligations. Additionally, individuals must be able to oversee the high-risk AI system, known as the human oversight requirement.

Limited risk AI systems, such as chatbots, must adhere to specific transparency obligations. The AI systems under this category must be clear about the fact that the person is interacting with an AI system and not a human being. The providers of such systems must make sure to notify the users of the same.

The users of biometric categorisation and emotion recognition systems must inform the natural persons who are being exposed to the system's operation. Meanwhile, users of AI systems that create or manipulate audio, photos or video content (deepfake technology) must inform others that the content has been artificially generated or changed.

However, these transparency obligations do not apply to AI systems used by law enforcement agencies that are authorised by law, as long as they are not made available to the public for reporting criminal offences:

Low or minimum risk AI systems encompass AI systems such as spam filters or video games that utilise AI technology but pose minimal to no risk to the safety or rights of individuals. Many AI systems belong to this category, and the regulation allows for their unrestricted use without any additional obligations.

AI from a liability perspective

The European Commission has proposed two sets of liability rules regarding AI – the Revised Product Liability Directive and the New AI Liability Directive – aimed at adapting to the digital age, the circular economy and global value chains.

The Revised Product Liability Directive will modernise existing rules on the strict liability of manufacturers for defective products to ensure that businesses have legal certainty to invest in new and innovative products, and victims can receive fair compensation when defective products, including digital and refurbished products, cause harm. The revised rules will cover circular economy business models and products in the digital age and will help level the playing field between EU and non-EU manufacturers. It will also ease the burden of proof for victims in complex cases involving pharmaceuticals or AI.

The core elements of the Revised Product Liability Directive include:

- Broader product definition: First and foremost, the definition of "product" is to be expanded and it is to be clarified that in the digital age, the term "product" also includes software and "digital construction documents" (aiming at 3D printing). Software is to be understood as a product regardless of how it is made available or used (exception: open-source software).

- Broader defect concept (liability reasons): A product is defective if it does not meet the justified safety expectations of an average consumer. In the assessment in individual cases, the objectively justified safety expectations and the presentation of the product are decisive. In the future, other factors must also be taken into account. The networking and self-learning functions of products are explicitly mentioned, but also cybersecurity requirements shall be considered.

- Extension of the material scope of protection: Up to now, personal injury (life, body, health) and damage to property, insofar as it occurred to a movable physical object different from the product, led to a claim for compensation. Pure financial losses, however, are not eligible for compensation. This restriction to fault-related violations of legal rights is maintained in principle, but certain extensions are provided. For example, the "loss or falsification of data that is not used exclusively for professional purposes" is defined as "damage" in the product liability regime for the first time. In relation to AI systems, this proposal means that in the case of damage caused by faulty AI systems, such as physical damage, property damage or data loss, the provider of the AI system or any manufacturer who integrates an AI system into another product can be held responsible and – regardless of fault – compensation can be claimed. In addition, medically recognised impairments of mental health are also to be regarded as bodily injuries.

- Expansion of the addressees of liability: In addition to the existing potential liability addressees (manufacturers, quasi-manufacturers, i.e. companies that mark products produced by third parties with their identifying marks, such as brand and name, and EU importers), further potential liability subjects will be drawn into the circle of responsible parties. On the one hand, the concept of manufacturer is expanded to include all manufacturers of defective products and component manufacturers in the future. This means that manufacturers of software and of digital construction documents and providers of "connected services" will also be included in the circle of potentially liable parties. It is noteworthy that the Product Liability Directive thus at least partially extends product liability to service provider liability. In addition, the manufacturer's authorised representative as defined by product safety law and the fulfilment service provider are to be liable for product defects in the same way as the manufacturer. "Fulfilment service provider" refers to companies that take care of shipping, return shipping, warehousing or customer service in e-commerce.

- Disclosure obligations / access to evidence for injured parties: The plaintiff bears the burden of proof for the damage, the defectiveness of a product and the causal connection between the two. To meet that obligation, they must present facts and evidence that sufficiently support the plausibility of their claim for damages. Due to the information deficit that consumers naturally have vis-à-vis manufacturers when using products, the draft provides for "access to evidence". Upon court order, the defendant must "produce the relevant evidence within their control". If the defendant does not comply with this order, they risk losing the proceedings because the defectiveness of the product is then presumed by law. In addition, the previous facilitation of evidence for injured parties will be extended. In future, the necessary causal connection between a product defect and damage will be presumed in favour of the injured party if the damage was caused by an obvious malfunction of the product during normal use. In this respect, the bar of proof for the injured party will hang relatively low if they wish to assert claims for damages against the manufacturer after suffering an accident while using a product.

The second proposal is the AI Liability Directive, which will establish broader protection for victims of AI-related damages and encourage growth in the AI sector by increasing guarantees. The directive simplifies the legal process for victims when it comes to proving fault and damage caused by AI systems. It introduces the "presumption of causality" in circumstances where a relevant fault has been established, and a causal link to the AI performance seems reasonably likely. The directive also introduces the right of access to evidence from companies and suppliers, in cases where high-risk AI is involved. The new rules strike a balance between protecting consumers and fostering innovation while removing additional barriers for victims to access compensation.

The proposed AI Liability Directive will have an impact on both the users and developers of AI systems. For developers, the directive will provide more clarity on their potential liability in case of the failure of an AI system. Individuals (or businesses) who suffer harm due to AI-related crimes will benefit from streamlined legal processes and easier access to compensation. The two key aspects are:

- Presumption of causality: The AI Liability Directive proposes a "presumption of causality" to simplify the legal process for victims when proving fault and damage caused by AI systems. National courts can presume that the non-compliance caused the damage if victims can show that someone was at fault for not complying with an obligation relevant to the harm caused and a causal link to the AI performance seems "reasonably likely". This allows victims to benefit from the presumption of causality, but the liable person can still rebut the presumption.

- Access to evidence: The AI Liability Directive will also help victims to access relevant evidence that they may not have been able to under the existing liability regime. Victims will be able to ask national courts to order disclosure of information about high-risk AI systems, enabling them to identify the correct entity to hold liable. The disclosure will be subject to safeguards to protect sensitive information, such as trade secrets.

AI from an IP lawyer's perspective

Other than to the regulator, IP issues specific to "AI" only arose more recently with the emergence of large neural network-type models and their training.

Since in many cases, the very essence of such AI is not having humans involved in their creation and activity, usual IP approaches of dealing with any other kind of software are partially invalidated here. Neither their training nor their output may require any human intervention or allow for human creativity to be involved.

In addition, their reliance on vast bodies of training data may pose IP risks, which, while not new as such, may affect an entire industry.

As laid out above with regards to AI and machine learning, creating a modern (neural network-type) AI requires vast amounts of data in order to train the subject AI model. Of course, this often involves crawling and scraping large parts of websites as well as online databases. This comes with some potential pitfalls from an IP perspective:

1. In most cases, such data predominantly include copyrighted works such as images, text, website layouts or the source code of websites.

The reproduction of which at the scraping client PC's data storage usually interferes with any right holder's exclusive right to reproduction as set out in Art 2 InfoSoc Directive (Directive 2001/29/EC) and Art 4 Software Directive (Directive 2009/24/EC) and its national transposition laws.

2. Web scraping may infringe exclusive rights in databases under the EU Database Directive (Directive 96/9/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 March 1996 on the legal protection of databases) in the following ways:

- Copyright infringement:

If a database is considered an original intellectual creation due to the selection or arrangement of its contents being creative and original, it may enjoy protection as a collective work. Unauthorised web scraping and thus reproduction of substantial parts of such would be subject to the same regime as any other copyrighted works scraped.

- Sui generis database right:

The Database Directive also establishes a sui generis database right in its Article 7, which protects databases that do not meet the originality threshold for copyright protection but involve a substantial investment in obtaining, verifying or presenting the data. Most databases may fall within this definition.

If a systematic arrangement of information made available to the public is scraped and reproduced, this would also interfere with the right holder's exclusive right to reproduction of databases enjoying protection as a sui generis database.

Of course, scraping parts of the internet is usually not a major part of the AI development process anymore, since large datasets of scraped and otherwise collected data are often made available free of charge.(eg. see commoncrawl.org)

However, retrieving any copyrighted works or protected databases via such readily available data sets does not mitigate the risk from an IP perspective, as acts of reproduction of any protected works included therein are still necessary.

There is no such thing as a fair use doctrine within the EU copyright regime, but directives (and respective national transposition) rather contain strict and narrow limitations that Member States may impose (e.g. Art 5 InfoSoc Directive). Defending such acts against infringement claims of right holders is potentially challenging.

In short: usually not.

Usually, software is mostly made up of source code written by human programmers implementing the abstract mathematical algorithm or business logic of the program. The written code may then enjoy protection as a copyrighted work of literature in any form (as binary, in object form or as source code) to the degree that such code is not determined by external (technical) factors but makes creative use of some leeway within the perimeter of the program's functionality and external technical limitations.

This is different for AI models:

1. Implementing code

Although code implementing the execution of an AI model may be protected by copyright, it is rarely of particular value, since code mostly relies on multiple open source databases and any AI model (which is almost always stored as a separate file) could often be executed based on independently developed code with relative ease.

2. The model itself

However, AI models do not usually provide any room for creativity on the part of the data scientists creating them. The overall architecture is to a certain extent determined by humans. The resulting design of the architecture (which form of neural network is to be used, how many parameters/weight and bias values should the model have, etc.) is almost entirely driven by the attempt to achieve a more precise result, leaving almost no margin for creative decisions that would not diminish the output of the trained algorithm.

In addition, the training of the model often requires immense capital in the form of computing power, resulting in a trained model that produces desired results. Aside from this being entirely optimisation-driven (leading to the same result when the machine-learning algorithm is run again on an untrained model), the training occurs automatically. However, as only works created by a human individual may enjoy copyright protection in most jurisdictions (including Austria), there is no copyright protection for a trained model.

1. Know-how

In many cases the main means of protection for a valuable AI model will be mere know-how protection based on confidentiality. All parties having access to the model would have to be contractually bound to refrain from any acts endangering exclusivity in such a model (such as reproduction and disclosure to third parties).

To avoid the unauthorised reproduction of any trained models, such are usually not provided for download but via API or an online interface. In that way, any user may only enjoy the functionality of a particular model while having no access to the enabling and valuable AI model.

In case confidentiality is effectively safeguarded, the trade secrets regime imposed by the Trade Secrets Directive (Directive (EU) 2016/943) and their national transpositions concers some protection against unauthorized use. This regime also allows for a legal remedy against third parties to which such a confidential model has been disclosed in violation of an NDA, while being aware that such access likely violated the discloser's confidentiality obligations.

2. Patents

Any inventions in all technical fields that are novel may be patented according to Austrian patent law and the European Patent Convention. To a limited degree, certain aspects of AI models concerning their architecture and the way they are used may be patented if they

- achieve a certain technical effect, usually meaning a certain interaction or relation to the physical world (e.g. use of a certain architecture for behaviour of a robot);

- are novel, in that such use of an AI model has not been published before; and

- are inventive, in that the average skilled artisan would not have found the claimed solution obvious when confronted with the same technical problem.

This approach, however, is limited by multiple factors:

- protection of any patent is limited to the particular use claimed in the patent (as AI models as such cannot be patented, since they do not display any technical effect by themselves);

- the trained model may not be patented (only aspects of its architecture and the training process), since any patent requires the full disclosure of an executable form of the subject matter claimed in the patent;

- AI models that may be used by cloud services may not be inspected by a patent proprietor, therefore limiting effective enforcement options.

The rise of generative AI, in particular diffusion models such as Stable Diffusion and Midjourney (creating realistic images) as well as large language models such as GPT4, are taking the world by storm with their apparent creativity and increasing accuracy.

In particular, large language models seem to be capable of much more than generating entertaining texts and helpful suggestions for coding software. OpenAI has reported impressive abilities of GPT4 in drug discovery.[1] DeepMind's AlphaFold (although not a large language model) has demonstrated a fascinating capacity to predict the structures of proteins, thereby helping to discover proteins with novel and desired properties.

All this shows that information and works generated by AI can be of considerable value, necessarily raising the question of whether such works may enjoy protection. The most prominent and important questions here concern copyright and patent law.

[1] https://cdn.openai.com/papers/gpt-4-system-card.pdf, pp 16 et seq.

At least Austrian copyright law requires a human creator whose decisions and input lead to a creative and original work. Therefore, any works generated entirely by an AI would not enjoy protection under the Austrian copyright regime.

In reality, however, the situation is not always so clearcut:

- If the AI merely follows the creative instructions of the user (provided via "prompt", being a series of instructions describing the desired output addressed at the AI model), such input alone may confer to the user a copyright in the results provided. In this case, it is the user acting as the creator of the original work, using the AI as a tool to achieve this.

- Also a user may not merely accept the first output provided, but may heavily edit such or integrate to output or multiple outputs into a creative arrangement. Also, in such case copyright protection could be conferred as far as the user's creative input alters the original output.

As already laid out above, according to Austrian law any technical teaching may be patented under Austrian patent law as long as it is novel, inventive and commercially applicable. However, there is some discussion internationally about whether a technical solution created by an AI is or should be patentable.

- Austrian Patent Act (APA)

Sec 1 para 1 APA defines an invention by merely objective criteria irrespective of any human intellectual effort necessary for an inventive step. However, pursuant to Sec 4 para 1 APA, inventorship serves as a starting point for the right to be granted a patent. Thus, in theory, an invention may not be patented if there is no human inventor involved at all.

At least according to Austrian law, the inventor must always be a natural person who discovered the main inventive idea behind a patentable invention by creative conduct. This is mainly of relevance under Austrian patent law, as only the inventor (and their legal successors) are entitled to be granted a patent. It is disputed whether such a finding must be the result of wilful creative conduct by the inventor, and one may easily argue that any natural person operating the AI, and thus discovering the technical solution proposed by the AI, may be deemed the inventor.

However, even if no inventor is determined, this would not preclude the patentability of the invention. Pursuant to Sec 99 para 1 of the Austrian Patent Act, the Austrian Patent Office will not examine whether the subject applicant of the patent is actually entitled to be granted a patent for an invention mostly made by AI. As there is no legal remedy under the Austrian patent regime based on the mere absence of a human inventor, any such patent can hardly be challenged on such grounds.

- European Patent Convention

The question of inventorship is slightly more relevant with regards to European Patent applications. The Board of Appeals of the European Patent Office has already laid out (EPO BoA J 0008/20) that it is mandatory to designate a human inventor according to Article 81 EPC. Thus, any application designating a program or no inventor at all would be rejected. However, as the BoA expressly pointed out, this may ultimately make no difference with regards to overall patentability, as no provision would prevent any applicant from simply naming the user of the AI as the inventor.

Of course, in the same way as AI models themselves, any AI's output may be kept confidential and thus enjoy limited protection against third-party use under the Austrian (and EU) Know-how regime.

Furthermore, certain other IP rights do not require a human creator, in particular most ancillary copyrights (such as sui generis database protection) as well as trademarks. In these cases the output may indeed be protected by such IP rights without the need for human invention, if the other requirements (investment, registration, etc.) are met.

- If an AI reproduces copyrighted works that it "memorised" from its training data. The mere fact that such original work is reproduced by an AI does not make the interference with the original author's reproduction right less relevant.

Example of an AI reproducing copyrighted works: ChatGPT provides a pre-existing work of literature upon a user's request.

This problem is the basis of some controversy as regards recently released powerful generative AI tools such as Stable Diffusion, Midjourney or GitHub Copilot/Codex. Diffusion models in some cases deliver images closely resembling copyrighted images that are part of the training data. GitHub Copilot produces code snippets almost identical to code found in other programs made by human programmers.

- Modifications/Translation

The best example of this would be any automated translation service. Here the user provides an originally copyrighted text to the AI model, which simply translates the subject text, while leaving large parts of its semantics and structure untouched. As the main creative traits of the original work are thus preserved, the mere fact that an AI edited the work does not necessarily devoid it of any copyright.

AI from a C-level perspective

AI is transforming how businesses operate, from automating routine tasks to optimising business processes and decision-making. For executives in the C-suite, it is essential to understand the implications of AI on the overall corporate strategy, organisational structure and revenue growth.

Here is a breakdown of five benefits and five risks of AI from a C-level perspective:

AI's ability to process large amounts of data and deliver insights quickly enables organisations to stay ahead of their competitors. C-level executives should understand that adopting AI technologies can provide a competitive advantage by speeding up decision-making processes, improving customer experiences and optimising operations.

AI can reduce operational costs while streamlining business processes. This is achieved by automating routine tasks, improving resource allocation and optimising supply chains.

AI can open up new revenue streams by analysing market trends and customer preferences and creating tailored products and services. C-level executives should explore how AI can identify untapped market opportunities, improve product and service offerings, and drive revenue growth.

AI can improve risk management by predicting and mitigating potential risks, e.g. in detecting fraud and cybersecurity threats. For C-level executives, the use of AI technologies can lead to better risk assessments, reduced vulnerabilities and improved regulatory compliance.

AI's ability to analyse customer behaviour and preferences enables the personalisation of products and services, increasing customer satisfaction and loyalty. At the same time, the automation of routine tasks allows employees to focus on higher-value, customer-facing tasks, increasing productivity and engagement. This synergy between tailored customer experiences and engaged employees drives revenue growth and a vibrant corporate culture.

AI can inadvertently perpetuate biases present in training data, leading to unfair or discriminatory outcomes. The unethical use of AI can cause lasting damage to a company's reputation. C-level executives should not only be aware of the potential risks associated with AI bias, but should also be the ethical gatekeepers of the company and ensure that AI technologies are developed and implemented ethically.

AI can generate and analyse vast amounts of data, which raises questions about the ownership of and the right to use that data. The intellectual property of AI-generated content is another significant challenge. To avoid legal pitfalls, C-level executives should understand the intellectual property issues associated with AI, including data ownership, copyright and patent considerations.

AI systems often rely on large amounts of data, which can create data security and privacy risks. C-level executives should ensure that their organisations have robust data protection measures in place and are compliant with data privacy regulations.

AI-generated decisions and actions can pose legal risks, especially when autonomous systems are involved. For example, an automated trading system that executes high-frequency trades could inadvertently cause significant financial losses. C-level executives need to be aware of the potential liability risks posed by AI technologies and ensure that their organisations are equipped to deal with these risks.

Overreliance on AI systems can lead to a lack of human oversight and judgement, potentially resulting in sub-optimal decisions. Automation can lead to a decline in human skills, impacting the long-term adaptability of the business. C-level executives should strike a balance between automation and human involvement to maintain organisational flexibility and adaptability, and prioritise employee development and skill-building to ensure continued success in a rapidly changing business landscape.

AI from a head of legal perspective

As a head of legal, understanding AI and its implications is crucial. AI is now an integral part of many business processes, bringing both benefits and legal challenges. Below you will find key takeaways to help you navigate the complexities of AI from a legal perspective.

AI technology is not a distant concept, but an actual reality that has already become an integral part of our business lives. AI tools assist in many areas, including personalised recommendations, fraud detection, machine translation, texting, logistics and much more. You should be aware that your business is likely already using AI in some form, and you should be prepared to manage the legal implications associated with it. As AI technology continues to evolve, future routine software updates will soon bring further AI-enabled improvements to your organisation's systems. However, with these benefits come potential legal challenges related to privacy, ethics and compliance with local and international regulations. It is important that your company understands the legal framework for AI and is prepared to address these issues as AI technology becomes increasingly integrated into the software ecosystem.

Existing regulations such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the NIS(-II) Directive and the Medical Devices Regulation already apply to AI applications in areas such as personal data protection, critical infrastructure and AI-based medical devices. As general counsel, you should ensure that your organisation is aware of and complies with these existing regulations. It is also essential to get familiarised with the basics of these legal regulations, as understanding the fundamental principles and requirements is crucial for effective compliance and risk management.

The proposed AI Act is intended to be the EU's first comprehensive, cross-sector regulation focused on AI. However, comparisons with initiatives in other countries (and continents), as well as comparisons with non-binding guidelines for responsible AI governance, show that regulatory approaches tend to be generally based on common principles, including privacy and data governance, accountability, robustness and security, transparency, fairness and non-discrimination, human oversight and promotion of human values. Understanding these principles can provide a solid foundation for preparing for upcoming regulations.

While compliance with existing and upcoming regulations is crucial, organisations should also adopt responsible AI practices that align with the common principles for ethical, trustworthy and human-centric AI. Implementing these practices independently from legal obligations demonstrates a commitment to the responsible use of AI and can build trust with stakeholders and customers.

The AI landscape is rapidly evolving, with new technologies, applications and regulations emerging. The world of AI can be intimidating and the terminology confusing. As a general counsel, you need to keep abreast of developments in AI technology and the regulatory environment. Identify your internal AI thinktanks and network with your IT (AI) project leaders to proactively assess the potential legal and ethical implications of AI applications in your organisation.

On 12 July 2024, the AI Act was published in the Official Journal of the European Union.

news

media coverage

Artificial Intelligence – Real Responsibility

This article was first published in Die Presse Recht Spezial, 21.05.2025

newsletter

What should employers expect from the EU AI Act?

Perspective of Serbia / non-EU country

newsletter

AI regulation and development in Serbia

AI is developing rapidly in Serbia and numerous initiatives are emerging daily. Therefore, a working group, which includes our Schoenherr expert Marija Vlajković, is already in the process of drafting a new Law on Artificial Intelligence. The final draft is expected by spring 2025.

newsletter

Privacy concerns in web scraping: a GDPR and Serbian privacy law perspective

When developing their models, AI providers use various data sets. Sometimes these are provided by their clients, as in the case of tailor-made chatbots, and sometimes the models are trained on licensed or even publicly available data. In both situations, the data sets almost always include personal data. Thus, AI developers should carefully consider their obligations under the GDPR as well as local privacy law, depending on what applies to them.

newsletter

The status and future prospects of AI regulation and development in North Macedonia

North Macedonia currently lacks AI-specific regulations, lagging behind neighbouring countries that have implemented guidelines or laws. Although the Macedonian Fund for Innovation and Technology Development (FITD) and the government initiated efforts in 2021 to create a National Strategy for AI (National Strategy), progress has been slow due to challenges such as insufficient data, human resources, and technical capabilities. Despite this, there is a strong commitment, supported by organisations like the World Bank and UNDP, to develop a comprehensive AI strategy aligned with European Union (EU) standards.

legal tech

legal tech

We integrate legal tech across five key domains: collaboration and transaction management, document automation, drafting and knowledge management, smart workflow tools, and AI/document review solutions.

Artificial Intelligence is shaping our world, and the way we conduct business, and it will continue to do so. With that, regulation and legal consideration will become more important as well.

Our AI Task Force, consisting of experts from various legal areas, is supporting you from start to finish in all your AI matters.

Contact us! We promise you won't get a chatbot's reply.

our team

Günther

Leissler

Partner

austria vienna

Alexander

Pabst

Attorney at Law

austria vienna

Thomas

Kulnigg

Partner

austria vienna

Daniela

Birnbauer

Attorney at Law

austria vienna

Miriam

Gajšek

Senior Associate

slovenia

Michal

Lučivjanský

Partner

slovakia

Dina

Vlahov Buhin*

Counsel | Vlahov Buhin i Šourek d.o.o. in coop. with Schoenherr

croatia

Natálie

Dubská

Associate

czech republic

Magdalena

Roibu

Managing Attorney at Law

romania

Vladimir

Iurkovski

Office Managing Partner

moldova

Marin

Demirev

Attorney at Law

bulgaria